A question on June 24, 2020:

Daniel,

I’ve come across some of your training online – quite informative – and was wondering if I could run a RCRA question past you. I have a client with some sodium-sulfur batteries that are no longer needed for their intended purpose. There are very few recyclers globally who can handle sodium-sulfur batteries and this is mainly due to the presence of sodium which is reactive and when thermally treated is detrimental to the refractory liner in the furnace.

We are exploring an option where we would reclaim the sodium from the cell, which can be used in, or to make, other products. In this case, would the company extracting the sodium require a TSDF permit? Based on the following logic, I would argue they are not a TSDF because the reclaimed sodium is not a hazardous waste. They would, however, be considered a waste generator with respect to the remainder of the battery:

- In order for a waste to be a hazardous waste, it must first be considered a solid waste (40 CFR 261.3).

- Sodium is a by-product of the chemical reaction in a sodium-sulfur battery – it is not present when produced at 0% SOC and is generated through chemical reaction when charging the battery and is consumed when discharging the battery. The process is not fully reversible so there is always some residual sodium present. For this scenario, where the sodium is desired to be extracted, it is more advantageous for the battery to not be discharged to 0% SOC.

- According to 40 CFR 261.2, Table 1, by-products exhibiting a characteristic of hazardous waste (sodium is reactive – D003) are not considered solid wastes when reclaimed. Per US EPA interpretations (which I have seen leveraged in your training) an analogy to this situation is a thermometer being reclaimed for its mercury. Because mercury is a Commercial Chemical Product, per 40 CFR 261.2, Table 1, it is not solid waste and therefore cannot be a hazardous waste.

- The act of extracting the sodium now makes the remainder of the cell waste and the generator (the entity who extracted the sodium) would need to classify it for its hazardous properties. Assuming it is hazardous, the generator would likely take advantage of the universal waste option for management and disposal.

If you have time and are willing, I would appreciate your feedback on the above.

Stay safe and well,

My reply seeking more information that same day:

Thank you for contacting me. Please see below.

- Q1: Is the battery a solid waste?

- Q2: If it is a solid waste, is it a hazardous waste?

- After that is determined, we can proceed to Table 1:

- Q3: What category of hazardous waste is it? (left-hand column of Table 1).

- Q4: What type of recycling are you practicing? (top row of Table 1).

Please clarify my understanding on the first two bullet points.

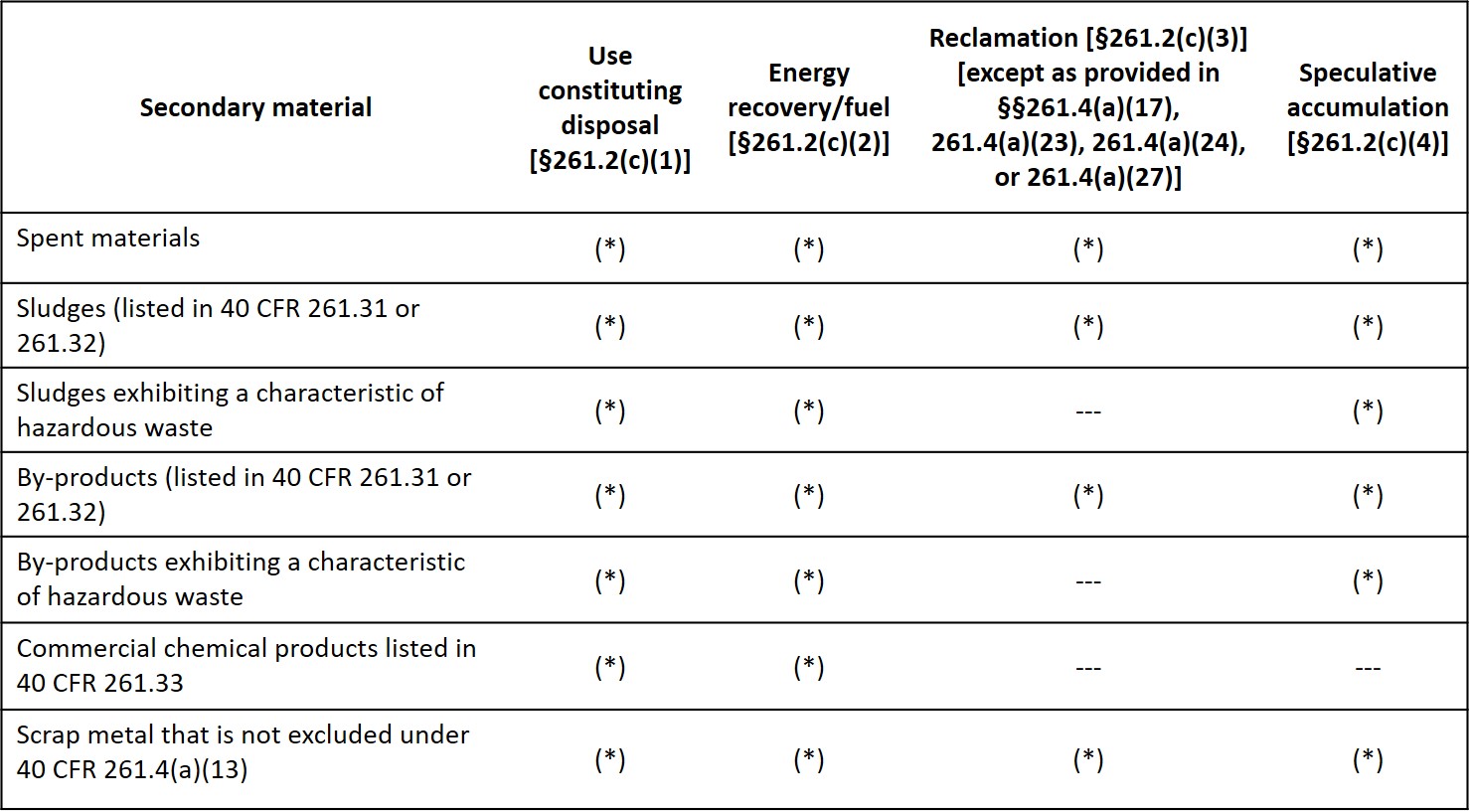

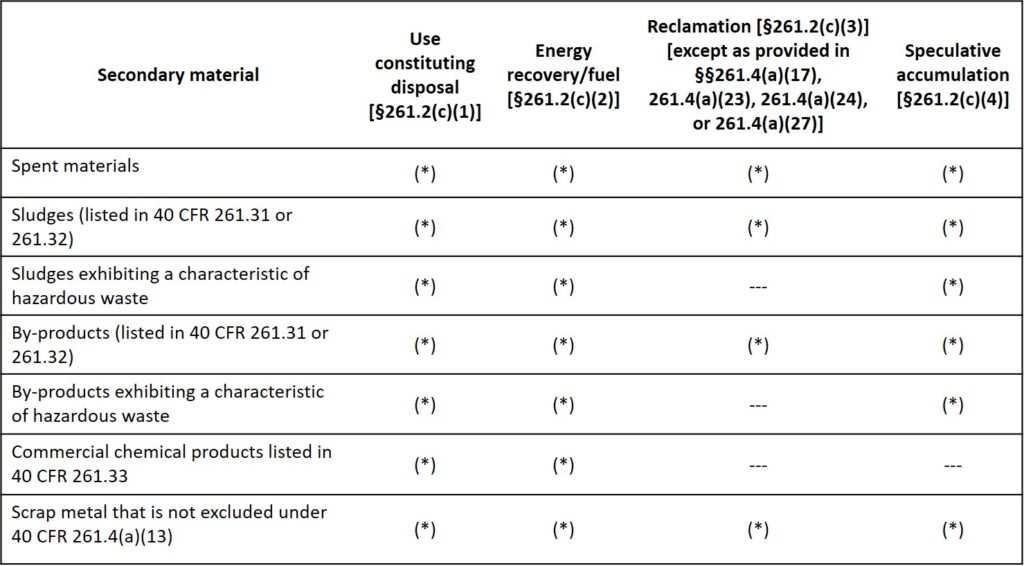

Note: an image of 40 CFR 261.2 – Table 1 is included below:

Read: Categories of Waste to Consider When Determining a RCRA Recycling Exclusion From Solid Waste

Like this article? Subscribe to my Monthly Newsletter No marketing emails! |

Back with more information:

Daniel,

Where I find the RCRA rules difficult is that there are two situations not one. There is the sodium and then there is the remainder of the battery. The questions do not allow this differentiation.

- Q1: Is the battery a solid waste?

- A1: Yes, because the battery will be recycled by reclamation.

- Q2: If it is a solid waste, is it a hazardous waste?

- A2: Yes, sodium possesses a hazardous characteristic – reactivity (D003)

- After that is determined, we can proceed to Table 1:

- Q3: What category of hazardous waste is it? (left-hand column of Table 1).

- A3: The battery would be considered spent, the sodium would be considered a by product.

- Q4: What type of recycling are you practicing? (top row of Table 1).

- A4: Reclamation. The battery will be smelted to recover metals for use in making products. The sodium will be reclaimed in its current form and used to make other products.

- Q3: What category of hazardous waste is it? (left-hand column of Table 1).

My reply:

Please see below.

- I agree that the battery is a solid waste. This is because it is being discarded. Recycling is a form of discarding.

- The presence of sodium does not by itself make the battery a reactive hazardous waste. The battery – not the sodium – when spent would have to display the characteristic of Reactivity (D003). Let’s presume it is a D003 Reactive hazardous waste.

- Table 1 contains some of the exclusions from regulation as a solid waste for materials that are recycled.

- It may be that the battery is considered to be a spent secondary material. However, the sodium is not a waste that is a by-product. It is part of the battery.

- If reclaiming, the reclaimed materials may be excluded from regulation as a solid waste and therefore cannot be a hazardous waste. This would mean the process of reclamation would not require a RCRA permit.

- Any waste generated during reclamation would have to be managed by the generator of the waste, that is, the person conducting the reclamation.

Please contact me with any other questions.

Later that same day with two more questions:

Thanks for your assessment. I would like to discuss further if you are open to it. My two follow-up questions:

- Given the scenario below would the entity reclaiming the sodium be considered a TSDF? Since it is not a hazardous waste I would assume not.

- While I follow your point, an intact sodium-sulfur battery does not demonstrate the characteristic because the cells are hermetically sealed. There is no possibility of water intrusion and thus no reactivity concern. The battery will be intact when it first becomes solid waste (abandon or recycled) but at some point in the process will demonstrate the characteristic because the cells will be breached. So when does the hazardous characteristic need to be demonstrated to be considered hazardous waste? I would argue that most intact industrial batteries do not demonstrate a characteristic hazardous waste when intact, yet nearly all are managed as universal waste (which inherently implies it demonstrates a hazardous characteristic).

I had more answers:

Please see below.

- If the battery is excluded from regulation as a solid waste then its recycling by reclamation would not require a RCRA permit.

- You’re correct that the hazardous waste determination is made at the point of generation for the entire battery. If the battery contains a reactive element (sodium) it would likely be a D003 Reactive hazardous waste.

I am available all day (06.25.20) to discuss. Can we schedule a time?

Contact me with any questions you may have about the generation, identification, management, and disposal of hazardous waste Daniels Training Services, Inc. 815.821.1550 |

Some more discussion took place over the phone (no transcripts available) but then another email on July 5th:

Daniel,

I hope you enjoyed the Independence Day holiday. I had a follow-up question on the definition of a commercial chemical product (CCP). RO 14012 states “For purposes of Section 261.2, CCP means all types of unused commercial products, whether chemicals or not.” The mercury thermometer example refers to new, off-spec thermometers. In my case, I have a used battery from which we will reclaim the sodium (which recall is produced through a chemical reaction during battery charging).

Through RO 14012, I found reference to an EPA memo which provides checklist to assist in evaluating whether CCPs are hazardous waste under the RCRA. In that memo, they state: “In the RCRA hazardous waste management regulations the term commercial chemical product generally refers to materials that would, under usual circumstances, be considered products and not wastes…”. It doesn’t specifically state ‘unused’ but rather “product”. I would argue that the reclaimed sodium from a used battery is useable product, which is also consistent with the definition of reclamation in 40 CFR 261.1(d).

I’ll submit this to state regulators but was curious of your opinion.

My reply July 06, 2020:

Please see below.

- You are correct – and something I should have mentioned – that for the purposes of the recycling exclusions at 40 CFR 261.2 a commercial chemical product must be unused. The batteries you are considering are used and therefore are not eligible for inclusion with CCP as defined at 40 CFR 261.2.

- Also, from McCoy Guidance: “Although Table 1 in 261.2(c) specifies ‘commercial chemical products listed in 40 CFR 261.33,’ EPA interprets the term to also include those products that are not listed in 261.33, but exhibit one or more characteristics of hazardous waste. [April 11, 1985; 50 FR 14219, RO 11713, 11726, 13356, 13490, 14883] So, a battery could be a CCP per 40 CFR 261.2 but only if unused.

- I believe the USEPA memo you refer to confirms the requirement the CCP be unused, “…would…be considered products and not wastes…” If it does not state unused here, it clearly does elsewhere.

- I don’t believe the status of the sodium in the battery or how it is recycled is any longer an issue. If the battery is not CCP per 40 CFR 261.2, it is not subject to the exclusion no matter how it is recycled.

Please contact me with any other questions.

If you like this article, please share it using any of the social media platforms identified at the bottom of this article. You’ll look real smart recommending my articles! |

No further communication after that – at least not yet.

It’s clear to see that knowledgeable persons can disagree about the exclusions from regulation in RCRA. In this situation I think the questioner did not fully understand that the hazardous waste determination – and thus any exclusions from regulation – begin at the point of generation. Subsequent treatment of a waste does not affect it’s eligibility for exclusions from regulation. But, perhaps, I wasn’t understanding his situation properly. It takes knowledge and careful research of the regulations to make a hazardous waste determination.